Born in the spring of 2004, the fine bay Thoroughbred colt is a grandson of Secretariat, the Triple Crown winner in 1973; and a great grandson of Bold Ruler, the 1957 Horse of the Year. Northern Dancer and War Admiral are also in his lineage. The colt showed promise as a 2-year-old, winning his first race at Aqueduct, the prestigious New York track. Like his ancestors, he too seemed destined for greatness.

But there is no such thing as ‘a sure thing’ at the track. That’s why it’s called a horse race.

As a 3-year-old, the colt apparently suffered a career-ending knee injury. Still, he was one of the lucky ones. He showed up for sale a year later at a respected hunter barn in Aiken, then again in Camden, where he caught the eye of Mary Werning, a top dressage trainer. Werning was impressed with the big bay horse. She felt he had potential in the dressage ring – not the worst place a washed up race horse can end up.

While the horse made an impressive appearance, he turned out to have some behavioral issues that potential buyers may have seen as insurmountable for the show ring. But Werning was fond of him and didn’t want to unload him to just anyone. She convinced a friend to buy him, and he spent the next two years grazing in the friend’s pasture interrupted only by the occasional trail ride.

The horse’s name is Axel Rhodes.

Last winter, horsewoman Shannon Burnett, who owns a farm with her husband, Chris Knierim, in Blythewood and is a partner in the law firm of Burnett and Cairns, was looking for a new dressage horse. She consulted her trainer, who happened to be Mary Werning. Werning suggested Burnett try Axel who was by then 7 years old.

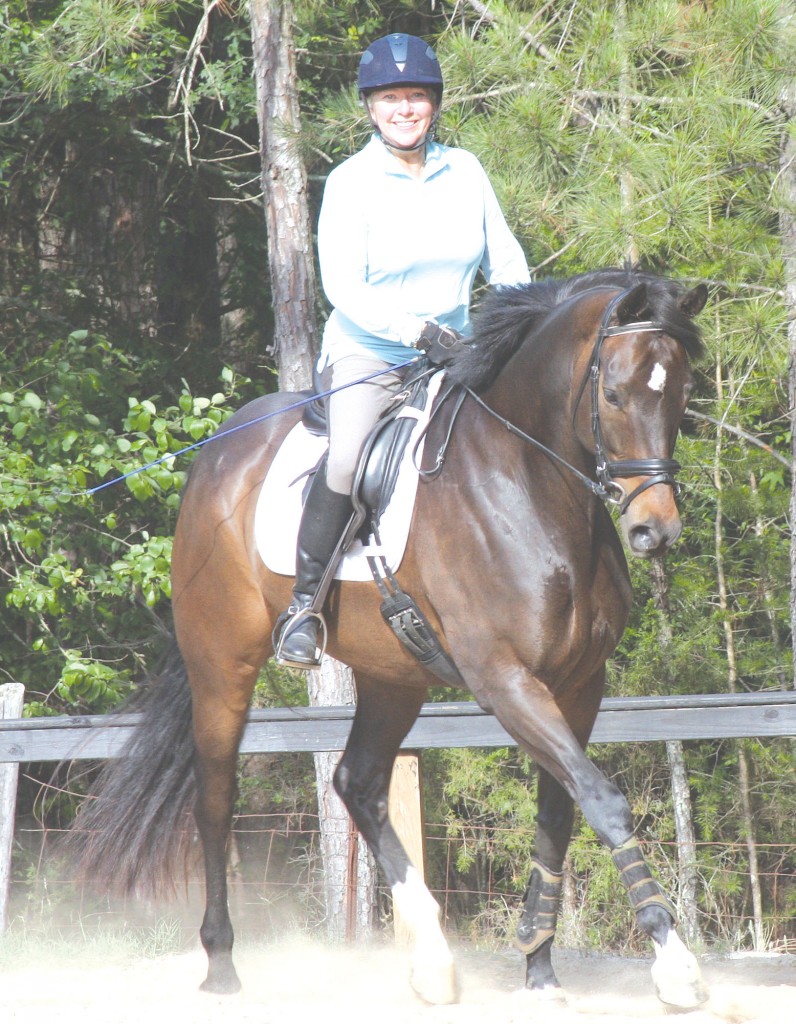

“He was big and beautiful — just what I was looking for,” Burnett recalled cheerfully of seeing the horse for the first time. “He looked more like a beefy Warmblood than a fragile Thoroughbred, and I liked him immediately. But when I got in the saddle, he was stiff, clinched the bit and seemed disconnected from what I was asking from him.”

Like the perspective buyers before her, Burnett just as immediately had second thoughts about the horse.

“Dressage is a discipline that requires fluid, subtle movement and a close relationship between horse and rider, just like ice skating partners. Dressage is like dancing. The horse must be very connected with you and he must love the dance. With a trained dressage horse, those movements,” Burnett explained, “are made in response to barely perceptible hand, leg and body pressure signals from the rider. I wasn’t convinced that was where Axel’s strength would ever lie.”

In spite of Burnett’s misgivings, Werning insisted he had great potential. She felt Burnett was the rider to bring out that potential and suggested she work with him for a month or so.

While Burnett trusted Werning’s instincts, she worried that Axel’s fate was sealed by his inability to connect.

“Thoroughbreds are naturally sensitive, and the gruelling discipline and work at the track can leave horses not only broken physically at a young age, but emotionally checked out as well,” she said. “Some just don’t make the transition well to new jobs when their racing career ends.”

A kind-hearted animal advocate whose two dogs, Felon and SueMe, sleep under her desk at her law office in downtown Blythewood, Burnett’s trademark calm demeanor and endless patience transmits quickly to her animals. By the second week of working with Axel, Burnett noticed him following her with his eyes as she walked around the barn.

“He seemed both smart and clever. He started coming to me from the paddock,” Burnett said, “and was soon following me around. Before the month was out, he was trotting up to me and then alongside of me. I could see his potential blooming.

“In the riding ring, I asked him to do things the same way each time, consistently and without stressing him. It wasn’t long before he realized I was communicating with him with my hands, seat and legs,” Burnett recalled with a smile. “As soon as he realized that he could do what I was asking, he immediately began answering with everything he knew. He was like: Do you want me to do this? How about this? He was enjoying the dance!”

She bought the horse and, before long, both horse and rider were training in earnest.

By the end of last summer, the pair had entered their first low-level dressage competition, winning both classes they entered. Burnett was ecstatic. Suddenly, she and Axel had plans, big plans.

Then in October, Burnett began noticing something different in Axel’s movement and behavior — something that worried her.

“He began to stomp and kick in his stall. He would sometimes put one hoof on top of the other and he would stand there on his own hoof without realizing it. He bounced his head up and down a lot, and his balance was off,” Burnett said. “He didn’t seem to know where his hind hooves were.”

She asked her veterinarian to examine him. After neurological tests and blood work, the vet’s diagnosis was not good. There was a high probability that Axel had contracted Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis (EPM), a progressive, potentially deadly disease caused by a protozoa infestation of the spinal cord and brain. Usually transmitted to horses by opossums, the disease is not easy to positively identify without surgery of the spine or brain. While it is not contagious between horses, there is no cure.

The veterinarian explained that while in rare cases a horse’s immune system will fight off the protozoa, most do not. She told Burnett that the medications she prescribed would only kill the adult protozoa.

“My heart was broken for Axel,” Burnett said. “I felt he was just starting to dream new dreams. We had big plans.”

But by that evening, Burnett had marshalled her heartbreak and hit the Internet. She found a biochemist in South Dakota who specialized in holistic treatment of horses with issues such as EPM, without the use of typically prescribed drugs, which the biochemist explained can be caustic. “I kept her on the phone until about 10:30 that night,” Burnett said.

The biochemist’s approach would fight the protozoa by strengthening Axel’s immune system. That meant switching to a special grass-based feed and supplements the biochemist would create after doing a hair analysis and gathering other information about the horse.

“Traditional veterinary medicine, of course, is not sold on this approach, and I understand why,” Burnett said with a shrug that reflected her own worrisome, underlying concern as she dumped the expensive special feed into Alex’s feed tub. “This may be voodoo,” she confessed, “but I have to try it.”

Burnett’s hope was buoyed when Axel began showing marked improvement within two weeks of starting the treatment, the projected time table mapped out by the biochemist.

“Now, three months later,” Burnett said, as she turned Alex out in the paddock on a recent cool, crisp afternoon, “he continues to improve and acts like his old self again, trotting along beside me and enjoying our rides.”

With her fingers crossed, Burnett said Axel’s training has resumed and is going well. She plans to start competing him again in the spring.

“We just work on the level that he’s comfortable with right now,” she said. “He always steps up to the plate and seems to say, ‘Let’s do this.’ Pretty amazing guy!”

Watching her horse rip around the paddock like a playful colt, Burnett joked, forever optimistic, “I hope the voodoo works. I think this is really his best hope, long term,” she said, turning thoughtful. “He’s forever missed his chance at greatness on the track. But he can still have a great life and make his grandpa proud in the dressage ring. Anyway, he’s depending on me for another chance, and I can’t let him down.”