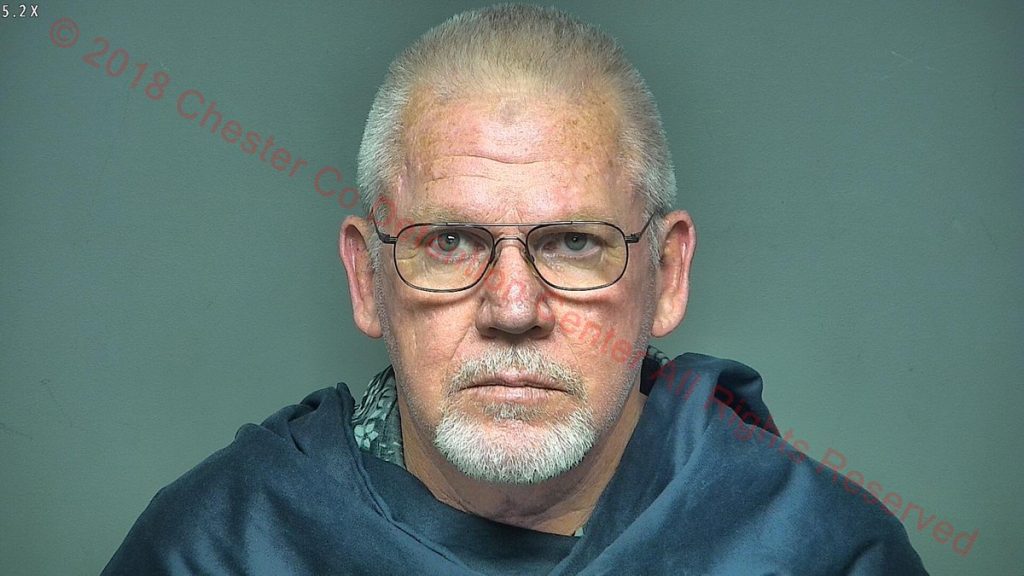

Lack of Cooperation, Investigation Took Center Stage at Trial

CHESTER – The lack of cooperation that took place between various agencies related to the death of Judy Baldwin, and the seeming lack of investigation by the Chester County Sheriff’s Department took center stage during much of her husband’s murder trial.

Jamie Baldwin was found guilty of murder in the December 2016 death of his wife Judy (read “Baldwin gets life for murder of wife”). Chester County Coroner Terry Tinker took the stand early Wednesday. He said for many months as he pursued this case, he only had “half the story” because he “never had any help from the sheriff’s office.” He said his relationship with the department’s detectives was always good, but that Alex Underwood (who has since been suspended from office on an unrelated matter) “was not ever willing to help me at all.” After “months of struggling,” Tinker said he approached Judge Brian Gibbons for help.

“I told him I was having trouble with the sheriff and maybe the sheriff was having trouble with me. I told him I was dragging this ball and chain by myself,” Tinker said.

He asked Gibbons if he could call and facilitate a meeting between all involved parties. He did, bringing together Tinker’s office, Underwood and three of his deputies, the Sixth Circuit Solicitor’s office, officers of the State Law Enforcement Division (SLED) and the South Carolina Highway Patrol. Tinker said that meeting helped in general, but not with Underwood specifically.

“From that day forward, without the help of the sheriff, we moved forward to where we are today,” Tinker said.

Sixth Circuit Deputy Solicitor Candice Lively asked if, given Baldwin’s history of having worked for the Chester County Sheriff’s Department, it would have been a good idea to bring in an outside agency like SLED to help with the investigation. The agency’s attendance at the meeting with Gibbons marked its first real involvement in the case. Tinker said (as did former deputy Chris Reynolds on Tuesday) that it would have. During cross-examination, defense attorney Phillip Jamieson noted that Tinker had stated earlier that he had known and been friends with Judy for years and had spent two decades working with her first husband, the late Todd Orr, at the Chester Fire Department. Given that close bond, Jamieson asked if Tinker should have recused himself from the case.

“You indicated earlier it would be better to have someone who doesn’t have a personal connection to the case involved. So shouldn’t you have removed yourself from the case?” Jamieson said.

“If they had tried to get SLED involved I would have removed myself, but they wouldn’t. So I had to stay involved,” said Tinker, who noted that he did have an assistant coroner by his side.

On Thursday there was testimony from Kay Black, a close friend of Judy’s. At a party, four days before her friend died, Black said Judy and Baldwin had an argument. Baldwin called her multiple times late that night after leaving the party and sent her a number of text messages (many of which were not allowed into evidence) detailing the argument. At one point, Baldwin called Judy “a stupid b***h,” stormed out of the house, slamming a door as he did and left their home, Black said. Judy told her that she tried to call Baldwin 30 times and he would not answer his phone. She tried to call one of her husband’s friends but he wouldn’t answer either. At that point she said Judy “was hysterical” and seemed on the verge of a breakdown. Judy told Black she was going to drive to the home of Terry King in York County to see if Baldwin’s car was in her driveway. Another witness in the trial identified King as Baldwin’s mistress, though King herself vehemently denied that allegation and said that she was just good friends with both of the Baldwins. Black offered to either come over to the house or to ride with her to York. She said Judy did not want her to do that as Baldwin would be angry if he knew she’d been talking to Black. In turn, Black told Judy to delete all of their text messages and calls from her cell phone so Baldwin would not see them. Black had all those texts and calls saved on her phone. She said she asked Reynolds (the detective working the case) if he wanted to see those texts after Judy died either at the hand of her husband or as a result of falling and hitting her head in her home, followed by a wreck on the way to the hospital.

“He said ‘no,’ that that wasn’t necessary,” Black said.

“Did he ever get a statement from you…a copy of your phone records” Lively asked.

“No,” Black responded.

Rodney Wright was Judy’s nephew. Like the rest of his family, he was shocked and devastated by her sudden death. The impact was even stronger when he entered the Baldwin home the next day. One of Judy’s sons lived just a few houses away and many family members had gathered there. Wright and his uncle were sent to fetch Judy’s dog. As the two entered the house, they saw the living room in which Baldwin alleges his wife fell and hit her head on the mantle.

“I was stunned at what I saw,” Wright said, referring to the amount of blood at the scene.

They found the dog which Wright’s mother (Judy’s older sister) would take custody of. That grisly scene stuck with Wright, though, and he became convinced something wasn’t right. He called Cpt. Phillip Perry at the Chester County Sheriff’s Department the day after Judy’s funeral and told him what he’d seen. Aside from 38 pictures taken just hours before Wright entered the home, no evidence would be collected from the house and the scene would be cleaned up hours after he fetched the dog.

“Did he ask you for an official statement? Was there a follow-up?” Lively asked.

“No,” Wright said.

He eventually went to the sheriff’s department to share his concerns with Underwood directly. He would never get the meeting he sought. He spoke only to Chief Deputy Robert Sprouse. Wright described the reaction he got as “short…like I was bothering them.”

Judy’s sister said she did get a call from Reynolds but it was to express “disappointment with people in Chester,” but said no statement was taken from her. King took the stand late Thursday and detailed that she received texts from Baldwin after Judy was injured and after the wreck. No one asked to see those texts in the wake of Judy’s death.

The lack of evidence collected at the scene was not just mentioned during the state’s case. Once the defense began its case, Ross Gardner was presented as an expert witness on blood spatter and forensics. While he disputed the testimony of state witnesses that argued Judy would have been dead within a few minutes of sustaining her head injuries (he said she was alive during the car wreck on the way to the hospital) he called the sheriff’s department’s work at the home, where Judy either fell and hit her head or was hit in the head by Baldwin, as “not up to snuff.” He offered a more blunt assessment during later testimony, calling it “trash.”

“You treat every unattended death as a homicide. There are questions these people deserve to have answered that cannot be answered,” he said.

He mentioned “holes in the data” and said the photographic evidence of the home was insufficient. There should have been hundreds of photographs taken and “the right kind of photographs taken.”

The state asked numerous witnesses, primarily current or former Chester County Sheriff’s Office employees if they knew of Baldwin having preexisting relationships with the office’s chain of command. The answers from varied, with some saying they did not know of any, to the possibility that friendships existed from Baldwin’s time working as a 911 dispatcher. The state did have a picture admitted into evidence showing Baldwin and members of his motorcycle club, presenting Underwood with a check for the Chester County Sheriff’s Foundation. Lively said the timing of the photo was important, since it was taken less than three months before the death of Judy Baldwin. She then referred back to testimony from Tuesday, noting that Reynolds said he didn’t do certain things related to the case (like pull phone records or mark off the home of the Baldwin’s as a crime scene to keep anyone other than law enforcement from going inside) because of the “chain of command.”

“I asked him yesterday who made those ultimate decisions and he said ‘Sheriff Alex Underwood.’ Terry Tinker had to bring in outside agencies (to investigate),” Lively said.

No deputy or former deputy that testified said they were directly told not to investigate Baldwin, though one said they were denied one request to seek a search warrant.

One piece of key evidence that never saw the light of day in the trial is the ladder that Baldwin alleged Judy fell off of and hit her head, ultimately leading to her death. One of the photos from the home showed the ladder leaning against a Christmas tree in the living room. That position would not have been consistent with the idea that she fell off in the other direction towards the mantle, but Wright and others also said the ladder was standing upright when they entered the house later. Baldwin’s defense team of Jamieson and Brad Jordan presented witnesses who claimed that Baldwin found a defect in the ladder, where the screws that hold the steps to the legs had partially pulled through. That could have caused a fall, they theorized. Baldwin, in fact, took that ladder to an attorney in Anderson County to inquire about a lawsuit against the manufacturer. Nothing came of that (it stayed in a closet in the lawyer’s office for many weeks), before Baldwin retrieved it. He claimed it was destroyed in a fire. It was never examined or collected as evidence.

Ultimately, the lack of evidence and initial cooperation did not derail the case.