The schools that emerged from Black Fairfield County were not named casually, nor were they named by default. They were named deliberately, often by the very students and communities the state underfunded.

In a system designed to limit expectation, naming became instruction.

Camp Liberty

Camp Liberty School functioned as more than a school. It was a launching point. In a county where educational access was restricted by policy and practice, Camp Liberty represented continuity and preparation.

For much of the early twentieth century, Black public education in rural South Carolina rarely extended beyond the elementary grades in practice, even when not capped by statute. Facilities, transportation, and sustained funding for Black students often ended after the early years. Advancement beyond that point required extraordinary effort, private tuition, or leaving the county altogether.

Education survived because communities organized it.

When Fairfield County built a new high school for Black students in 1954, the name was not assigned by an administrator or donor. An essay contest was held among Camp Liberty students asking them to write about native educators of Fairfield County.

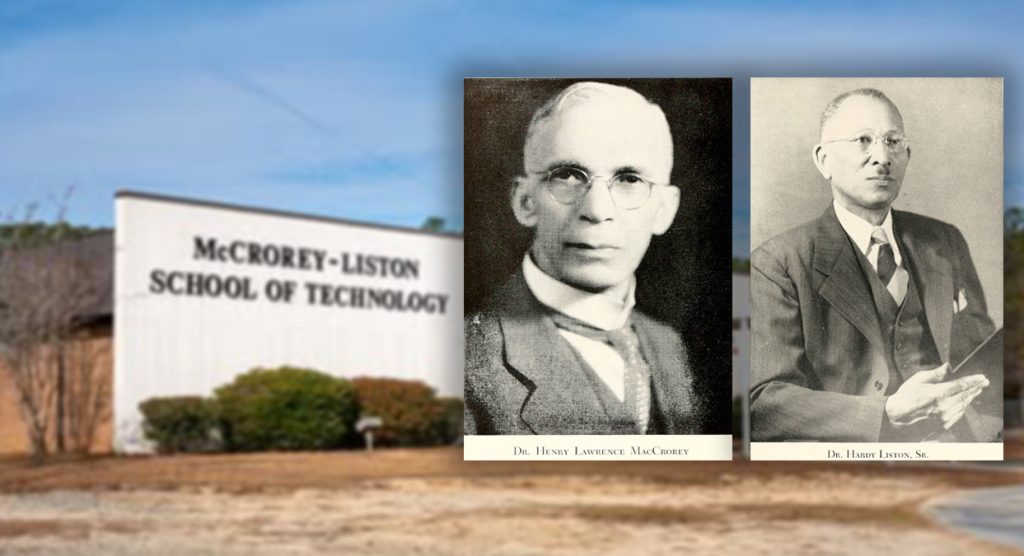

Two essays tied for first place. One honored Henry L. McCrorey. The other honored Hardy C. Liston. The school was named McCrorey Liston.

That decision matters.

In a system that quietly narrowed Black educational horizons, naming a school after two presidents of a historically Black university was an assertion of values. It said that education was not merely about access, but about aspiration. Students were being taught to see themselves not as recipients of limitation, but as inheritors of intellectual tradition.

Henry L. McCrorey

Henry Lawrence McCrorey was born in Fairfield County in 1864 at the edge of emancipation and uncertainty. He rose from that beginning to become one of the most influential Black educators of his generation, serving for decades as president of Johnson C. Smith University.

McCrorey believed education was preparation for leadership. Under his tenure, the university expanded academically and physically, producing ministers, teachers, and professionals who would shape Black life across the South.

For Fairfield County students to choose McCrorey was to claim seriousness. It connected a rural beginning to national Black scholarship and affirmed that origin did not limit destiny.

Hardy C. Liston

Hardy Clifford Liston followed McCrorey as president of Johnson C. Smith University, continuing leadership during a period when Black higher education faced constant financial and political pressure.

Liston represented stewardship. Where McCrorey symbolized ascent, Liston symbolized endurance. His leadership emphasized teacher training, institutional stability, and disciplined governance.

Naming a school after both men acknowledged that education was not only about brilliance. It was about continuity. It had to be built and maintained.

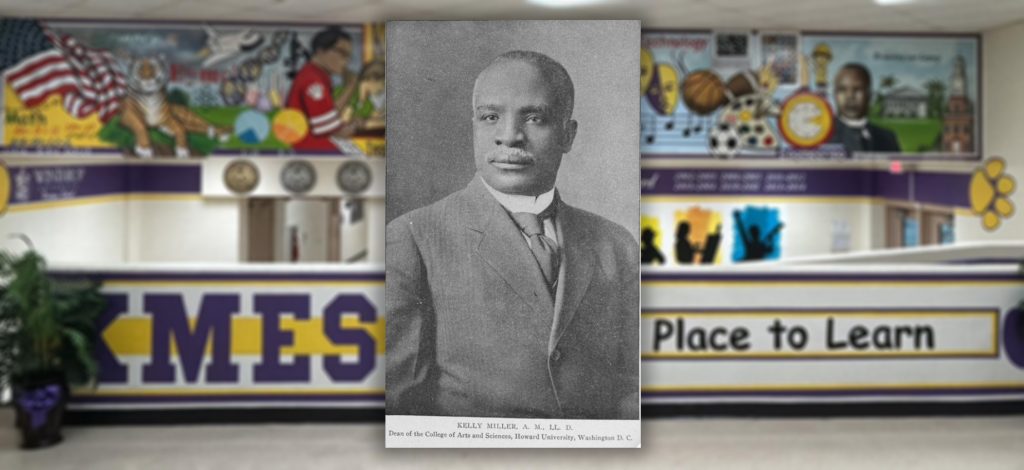

Kelly Miller

Kelly Miller was born enslaved in 1863 and became one of the most formidable Black intellectuals of the early twentieth century. He was the first African American to pursue graduate study in mathematics at Johns Hopkins University and later became a long serving professor and dean at Howard University.

Miller argued that education carried obligation. He rejected the idea that learning was merely a pathway out of poverty. Instead, he framed it as preparation for civic responsibility and public leadership.

A school bearing his name taught more than arithmetic. It taught that Black intellect was rigorous, visible, and accountable, even when the system around it was not designed to sustain it.

John A. Geiger

John A. Geiger represents the most common and least documented figure in Black educational history. The minister educator.

His work bridged church and classroom, faith and instruction. Men like Geiger taught where they could. Churches. Community buildings. Borrowed spaces. They sustained education at the point where formal support often stopped.

Naming a school after Geiger was not about prominence. It was about honoring daily labor. The kind that made advancement possible when continuation was never guaranteed.

Nellie M. Gordon

Nellie M. Gordon belongs fully within this lineage.

She arrived in Fairfield County in 1929 with professional training uncommon for the era, holding a Bachelor of Arts degree from Benedict College and a Master of Arts degree from New York University. She taught at Fairfield County Training School and remained there until a new elementary school was built in 1955.

When that school opened, the citizens of Fairfield County deemed it fitting to name it in her honor.

Gordon Elementary was not named by convenience. It recognized decades of disciplined instruction, professional excellence, and devotion to children whose access to education had always required protection. Miss Gordon devoted 37 years to education in Fairfield County, retiring in 1966 after shaping generations of students.

Her naming affirms that leadership also lived in sustained service. Authority was exercised daily in classrooms where standards were enforced and futures were quietly built.

Continuance

The tradition of naming with purpose did not end with those earlier generations. It continued.

In 2018, the McCrorey Liston cafeteria was named for Lugenia G. Wilson, known to many simply as Sis. She served the school for four decades, feeding students, steadying them, and shaping daily life in ways no transcript records. Former students returned as adults to honor her not because she held a title, but because she held the place together.

Lugenia G. Wilson was my great aunt. Securing the cafeteria in her name was not an act of nostalgia. It was an entry point. It was the first time I saw how memory, institution, and community action could align to produce something permanent. It marked the beginning of my own work in community development, grounded in the same tradition that named schools for educators and service for stewardship.

The lesson was consistent with everything that came before it. Recognition is not accidental. It is claimed. It is organized. And when done correctly, it becomes infrastructure for what comes next.

Naming as Curriculum

Taken together, these names form a pattern.

When Black Fairfield County had the authority to name educational institutions, it chose teachers, scholars, and builders of intellect. That choice reflects how education survived under constraint.