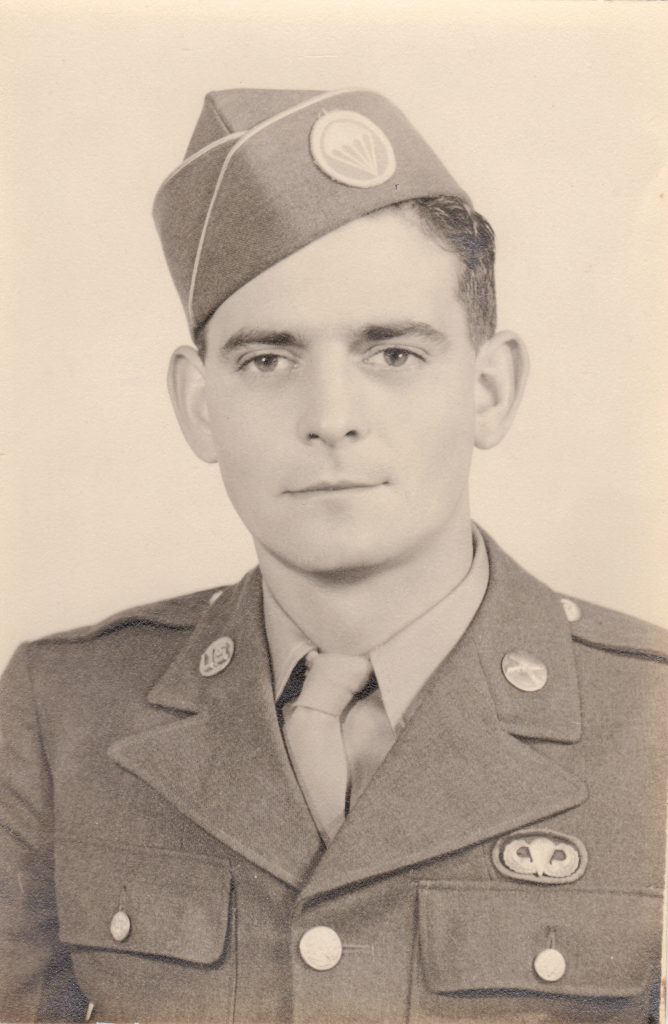

‘Longest Day’ Turned into Long Haul for Father of Publisher

Shortly after my dad, Bruce Baker, enlisted in the Army on Oct. 6, 1942, to serve in World War II, he learned paratroopers were being paid $100 a month more than the regular infantry, so he opted for the higher pay and the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment attached to the 82nd Airborne Division. While he had never even flown in an airplane, much less jumped out of one, he saw parachuting as an easy way to earn extra money for his young wife and infant son back in Texas.

Staff Sgt. Bruce Baker

In the predawn hours of June 6, 1944, he might have been rethinking that easy money as he scrambled to make his first combat jump out of a low-flying C-47 troop transport plane over Normandy, France under the most harrowing of conditions.

The day was D-Day – and that jump was the only one he would ever make.

The combined 13,000 paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were an integral part of the Western allies’ massive plan to liberate Europe from Nazi occupation and stop Hitler’s advance toward the west and, potentially, the world.

Those paratroopers were assigned what has been described by many historians as the most difficult task of the initial operation — a night jump behind the enemy lines five hours before the coastal landings. It was the greatest airborne assault in history at that time.

After making landfall, the paratroopers were to destroy vital German supply bridges, capture causeways and prepare the way for thousands of allied ships, aircraft and infantrymen that would arrive on the heavily fortified beaches of Normandy at dawn.

The 101st paratroopers (Mission Albany) were dropped first, beginning shortly after midnight, in three waves of about 1,800 each. They landed largely on target, northwest of Carentan, France.

The 82nd paratroopers (Mission Boston) were dropped next, also in three waves – the 505th, the 507th and my dad’s regiment, the 508th, was the last to jump. They were to drop west and southwest of the town of Sainte-Mère-Eglise. My dad’s regiment experienced the worst drop, with only 25 per cent landing within a mile of their drop zone. Half the regiment dropped east of the Merderet River, where they were useless to their original mission.

The problems for the 508th drop were myriad. The troop carriers were, by then, hindered by a dense cloud cover and increasing anti-aircraft fire, causing the troop carriers to break formation and stray off course. At the same time, the enemy began moving into the drop zones, delaying the pathfinder troops in marking those zones and causing the pilots of the troop carriers to overshoot the zones as they frantically searched for markers.

My dad later described the scene to my mom. When the green jump light flashed that morning, he and his fellow paratroopers dropped out of the open door of the aircraft into unimaginable chaos – dark skies, dense clouds, tracers everywhere and enemy fire. Plus, to avoid being hit by the enemy, the pilots of the troop carriers were maneuvering at greater speeds than would afford a good jump. My dad and many of the other paratroopers in the 508th landed widely scattered over the Normandy countryside, far from their jump zone and their well-planned assignments.

On July 24, my mom received a telegram informing her that my dad had been reported missing in action on June 11. My brother was 2 years old and I was due to be born two months later.

My dad later recounted to my mom how he and several other soldiers had been dropped into an area virtually surrounded by German troops and were captured five days after their boots hit the ground.

The Germans marched the captives for several days to a train depot where they were loaded into open-slatted railway cars. Because the tops of the cars were unmarked, they were strafed repeatedly by the prisoners’ own Western allies as they were transported to Stalag 12D in Berlin, one of two prison camps where my dad would be held until being liberated by the Russian allies on Jan. 31, 1945.

Of the 2,056 paratroopers in my dad’s regiment, 1,161 were either killed, injured or captured. While my dad survived the full blown, gut-wrenching glory that was D-Day and missed almost entirely the combat of the war, he did not escape the subsequent misery of starvation and other forms of deprivation and mistreatment he and his comrades endured in the prison camps.

In May, 1945, shortly before the war ended, my dad was joyously welcomed home by his family and friends in our Texas hometown that had then, and still has, a population of about 200. My brother was 3 years old and I was 8 months old. It was the first time my dad had seen me.

Quiet and laid back, my dad never appeared to carry much emotional baggage from his experiences. For the most part, he picked up where he left off before enlisting – hunting his wolf hounds by night and working in the North Texas oil fields by day. During the summers, he played baseball on a team with other men in our town on a hot, dusty sandlot they cleared off just outside of town.

In 1982, my dad died in Young County, Texas where he had lived his entire life. Virtually everyone in our town attended his funeral and burial which lasted most of the day.

While my dad never talked much to anyone about what he experienced on D-Day or in the prison camps, I grew up realizing that, for the adults in our town, the war was still fresh for years and years. They remembered and seemed to always have a special regard for my dad and the other men in our town who had gone to war, and for what they had done.

Today, on this 75th anniversary of D-Day, our friends and family back in Texas will, I’m sure, remember again – as will the whole of Europe, Great Britain, Canada and America. They, like all of us, will express gratitude for the soldiers who, on D-Day, risked everything to save us all from the unspeakable evil that spawned the war and threatened the world.

Just a few years later, Uncle Bruce was defending Santa Claus before a squad of skeptical nieces and nephews. He acquitted himself well. Then there’s the story his brothers told of him crawling under the house to shoot a noisy rattler. I still remember his kind eyes and soft voice.

Thanks, Barbara, for the recollections and tribute. Love to you, Ann C.

Amazing what that generation of brothers gave to our country. Bruce’s brother Bill served in the 76th Artillery which faught on the Western Front through the end of the war, including the Battle of the Hurt gen Forest. Another brother, Charles Dean, served as a gunner in the 707th Bomber Squadron losing an arm in combat. We owe them so much.