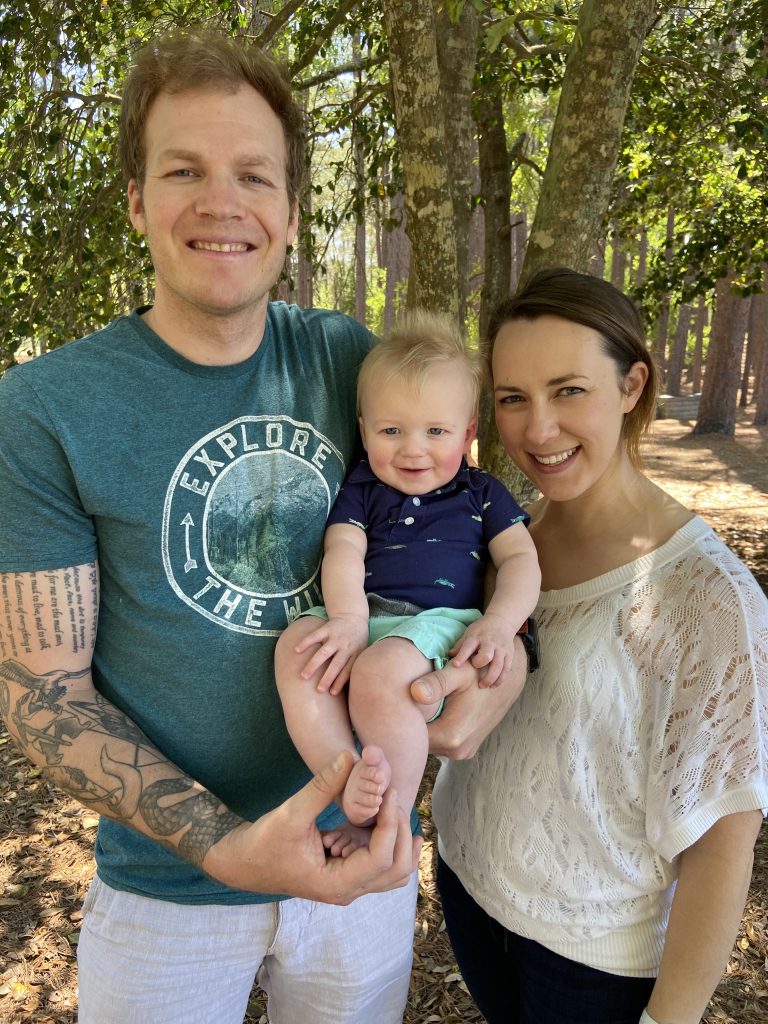

AFGHANISTAN – Nearly a decade after being caught up in a war crime investigation while serving in Afghanistan, David Zettel, now 33, and living in Blythewood with his wife Kim and their young son Declan, said the details of those horrific events are starting to blur, but not the reality of what happened.

“My platoon was sent to Afghanistan to help push the Taliban out and protect local civilians,” Zettel, said of his 2012 deployment, which he describes as largely a mission to win the hearts and minds of the villagers. “We were there for the locals. We were to help where we could.”

Instead, he said, he and his platoon were ordered to commit atrocities against the people they were there to protect.

Zettel’s platoon, which was part of the 82nd Airborne Division, had seen almost nonstop combat during their time in Afghanistan, and were about a month from the end of their deployment when Lt. 1st Class Clint Lorance was assigned to lead Zettel’s platoon, replacing an officer who had been wounded.

“It was evident to us from the first day that something was different about him. It wasn’t good,” Zettel said about Lorance who repeatedly shocked the combat-tested veterans with his mistreatment of the local population – the very people they were there to help – and thrust Zettel and his comrades into the midst of a war crime that eventually sent Lorance to prison and his men into a death spiral of guilt and confusion. Zettell said Lorance poisoned, in different ways, the lives and careers of the entire platoon.

Zettel said he is still haunted by the three days under Lorance’s leadership and will forever try to make sense of what happened.

The first red flag, he said, occurred the first day Lorence took charge. Zettel said Lorance, out of nowhere, threatened a soldier’s career because the drone the soldier was flying to observe the area, had a mechanical problem which he could not immediately fix. That same day, Lorance threatened to kill a farmer and his young son – a boy estimated to be 3 or 4 years old – after the man asked permission to move some wire a few feet so he could access his field. Zettel said Lorance also made false reports that the platoon had taken fire from the village. Then he tried to get members of his platoon and their Afghan allies to shoot at rocks that he claimed were IED’s.

Zettel said his testimony at Lorance’s subsequent trial related mainly to an incident that occurred the second day.

“I was in a guard tower when Lorence ordered us to harass locals with gunfire, expressing sadistic enjoyment at their frightened reaction,” Zettel said.

Zettel said he has agonized over the thought that, though he didn’t personally fire any shots, perhaps he could have said or done more to stop what happened.

“In the moment, it’s not as easy as what people think it is.” He said.

By the third day, Lorance claimed, falsely, that the rules of engagement had changed, enabling the platoon to shoot at anyone on a motorcycle – a common form of transportation in the area.

Later that day, Zettel said Lorance ordered members of the platoon to fire on three local men on a motorcycle, killing two of them without provocation. In the aftermath, they killed two more men in the village as well.

“It was by then obvious to us that Lorance had crossed a line,” Zettel said.

That day, soldiers in the platoon turned him in. After that, all those who had witnessed Lorance’s behavior over the three days were pulled into a months-long investigation in which the entire platoon lived under the threat of criminal charges, a nerve-wracking time, Zettel said.

In the end, after 14 members of the platoon testified against Lorance, he was sentenced to 19 years in prison for second-degree murder and other crimes – and the men of the 1st Platoon felt vindicated. But that didn’t stop the negative backlash against them when they moved on to future assignments.

On one hand, Zettel said, they were criticized for not doing enough to stop Lorance from committing his crimes. On the other hand, they were criticized for turning in one of their own.

Despite their intense, honorable service during their deployment – which saw several members of the platoon become seriously wounded – words like “traitor” and “coward” would come to haunt them.

But the major psychological blow came in 2019, amidst a flurry of politicized media reports supporting Lorance, President Trump granted him a pardon, and Lorance was released and treated like a hero as he arrived home from prison.

The story of the Afghan massacre, Zettel said, was distorted on Fox News. After Fox’s Sean Hannity encouraged Lorance on air to claim that the three men on the motorcycle were armed threats, members of the platoon pushed back, saying the three were villagers with only ID cards, scissors, some pens and three cucumbers in their pockets and had posed no threat to the soldiers, according to testimony.

The story of the pardon and the detail of the killings were widespread fodder on national news programs and newspapers, including a recent book by Anne Jacobson titled First Platoon: A Story of Modern War in the Age of Identity Dominance.

“It was tough to stomach,” Zettel said. Lorance’s conviction had been the only sign that someone was being held accountable, the only formal validation of the events that had left Zettel’s platoon wracked with guilt – the killings, the harrowing investigation that followed and the various forms of condemnation that they faced since.

As he prepares to leave the Army after more than a decade of service, Zettel said the killings and the aftermath have taken a toll on the men in his platoon. Five of them are dead. But these deaths didn’t occur on the battlefield; they happened after everyone came home.

Zettel said the men’s struggle to cope with what happened – the crimes, the investigation, the trial, the lack of support they received afterward and Lorance’s exoneration of sorts – took a heavy psychological toll on the men. Zettel said he believes it was the demons and haunting memories that pushed three of the five soldiers to their untimely deaths from suicide, drinking and drugs. Three others are reported to have attempted suicide.

“I’m not ashamed of what I and our platoon did over there. We did a lot of work. We helped the locals wherever we were. We pushed the Taliban out. We did our job to a very high level. I’m not ashamed of what we did,” Zettel said. “I’m ashamed of how we were treated for our service.”

“Once you start losing so many people to the demons that you’re dealing with yourself, and you know, when you start realizing that you could’ve done more, it just [messes] your world up,” Zettel said. “But what do you do?”

To escape the spiraling negativity after Lorance’s trial, Zettel went to college, earning two degrees in 2015 – in applied mathematics and economics – and became an officer. For the next four years, he served at New York’s Fort Drum, where he advanced from 2nd lieutenant to 1st lieutenant to captain.

But as friends he’d served with in Afghanistan died one after the other, he was not immune to their struggles. He acknowledges now that during that time, he drank far too much to shut out the memories.

Two years ago Zettel was transferred to Ft. Jackson. It was there that he decided to seek counseling and, ultimately, medication that he said has helped him deal with what has now been diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder.

After all he’s lived through, Zettel said what haunts him the most is the thought that he could’ve done more to stop the killings, more to help his friends overcome the demons that took their lives.

As Zettel waits for the paperwork to be complete for him to get out of the army, he’s starting to think about the future – perhaps become a master electrician, do data analysis or coding, work in industrial management, or perhaps something totally different. He said he has a lot of passions.

Today, Zettel said he tries to avoid anything that might dredge up painful memories. He acknowledges that he’ll probably never achieve peace inside his head. But that’s what he’s after on the outside, a quiet, happy family life.

Now, he said, he and his wife have a child to raise, and he wants to look forward.

Excellent story!! How refreshing to read a article of this caliber , in this local newspaper. Very well done Ms McCown